Santa Fe, New Mexico might conjure images of scorching desert, but in January, it can be colder than a cast iron toilet seat in Baffin Bay. It’s a dry cold to be sure, and by midday you find yourself peeling off layers and sometimes getting down to shirtsleeves.

It was a particularly cold January in 1988 when we were shooting YOUNG GUNS and having the time of our lives. Our long days were spent on horseback, filming in remote canyons, on the banks of the Rio Grande, or on the Native American land of San Ildefonso Pueblo, capturing the story of Billy the Kid and his Regulators. Our nights, all too short, were spent (mostly) at the Santa Fe Sheraton. We screened our dailies in a cleared-out first floor room. Cast and crew — still dusty and windburned from the set, smelling like horses and Fuller’s Earth — would cram in with cold Coronas to watch what we had shot two or three days before (this was in the days before dailies were handed out on iPads the very same day as filming).

After dailies, we’d gather in the Sheraton bar, mixing with locals, travelers, our local wranglers, stuntmen, and the inevitable influx of local girls staking out Emilio Estevez, Kiefer Sutherland, Lou Diamond Phillips, and Charlie Sheen. I was around the same age as those guys and enjoyed my tequila just as much. But it was my movie, a screenplay of labor and passion, and a part of American history that I embraced obsessively — so I walked a disciplined line as writer-producer. The guys would frequently come sit with me at a table to talk about their characters — particularly the true history behind those characters and the esoteric nooks and crannies of the background I had studied for years.

On this one night, I was sitting at a table with my wife and her best friend Joey, sipping Don Julio and relaxing after a long day’s shoot. All around us cast and crew decompressed at the bar and at tables while a local lounge band played contemporary hits.

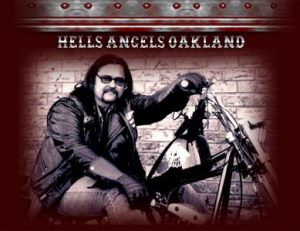

Always in the shadows of the bar were our P.A.’s (Production Assistants) who, in this unique case, happened to double as private security. They also happened to be members of the Oakland Chapter of the Hells Angels. Cisco Valderrama, who had been a Hells Angel since 1966, had been at Altamont, and would go on to become president of the Oakland charter, was always present as key PA/security. So was a bearded giant named Deacon Proudfoot and a few other fully-patched Angels, but we’ll get back to that. For now, just imagine the Hells Angels in their leather kuttes, hanging aloof by the bar, keeping us in their periphery.

I remember this night as the Curse of Billy’s Trigger Finger. Eating at my table, I was sharing with the guys some very recent research into Billy the Kid’s gravesite. All were invested in this information; the final scene of the movie focused on the fact that Billy was buried at Old Fort Sumner with two of his gang under the headstone inscription PALS. But as I was endlessly researching — even as we were scouting and shooting — I had come across recent evidence that theorized that Billy the Kid’s body had at one point been exhumed and relocated, and, by the calculations of one diligent researcher, was most likely now resting just off the highway, in the general area under the Santa Fe Sheraton.

Maybe right under us, right here, right now.

As the conversation went on, and we all inevitably drank more than we promised ourselves on a work night, the lounge band on stage announced that they were taking a break. One of the Young Guns — I think it was Kiefer (he drank single malt not tequila) — asked if he and a few others could take the stage, borrow their instruments, and play a few numbers. The local band graciously agreed and opened the stage to the popular young actors.

Somehow — I don’t remember how it happened — I went up on stage with them. I always had a harmonica in my jacket and the guys knew it. The improv group that assembled onstage was made up of: Kiefer Sutherland on guitar, Lou Diamond Phillips on vocals (La Bamba anyone?), Roger Cain (younger brother of Superman Dean Cain and son of our movie’s director) on lead guitar, and me, playing blues harp and trading vocals with Lou Diamond.

Although we had never played together before, there was a definite chemistry. Maybe because we had been deeply immersed in a dramatic and mythic storyworld together. Whatever jams we played drew more people in from the hotel and the lounge was soon packed. Nearly everyone was standing and getting close to the stage. There was a lot of dancing. Locals, wranglers, stuntmen, and crew. And then it happened:

I asked the guys to play a fast, Chicago-style blues in G. I leaned into the harp and pulled out some stuff from my earlier days on the road with blues-rock bands. One thing I had learned a long time ago — and tempted the fates with that night — was that when it’s getting late in a club and the booze has been flowing, BE CAREFUL WHAT YOU DO WITH A BLUES HARMONICA.

Whatever mojo was going on that night, we hit a hot and nasty groove and the sound was overdriven — in a good Junior Wells kind of way. The local band watched from barstools, equal parts amused and disgruntled as Lou channelled Ritchie Valens with an infusion of Chavez Y Chavez and Howlin’ Wolf. Kiefer was hammering on some other guy’s Fender, and Roger Cain was on fire (he would go on to become a successful musician). For the life of me I can’t remember who was on drums, but I was blowing Chicago harp in the high octaves and we had the crowd going wild.

During the dancing melee, a wrangler in full cowboy regalia, spilled his beer on the stunt coordinator’s girlfriend. Her name was Pam and she was an attractive older blonde from Santa Fe, always bedecked in fine turquoise and a New Age aura. She had met our stunt chief Everett Creech in town and the two had become an item. As John Wayne’s former stunt double, Creech was as legendary for his stunt stories as he was for his high falls and full-burns. But on this night he was enjoying the dance floor with his Santa Fe lady. So when some frothy Budweiser erupted onto her fringed, white, deerskin dress, she seethed. Everett, up in years but still in chivalrous John Wayne mode, edged in close. Pam took her own glass of red wine and poured it over the wrangler’s expensive Stetson. Merlot rained down off the large brim. The wrangler, wild-eyed, intoxicated, and electrified by the Young Guns blues performance, hauled off and slugged Everett in the jaw. Watching from stage, I saw it all and it almost had the raw, old-school choreography of a John Ford fight. Cowboy spills beer on girl; girl dumps wine on cowboy’s head; cowboy throws a haymaker and hits girl’s boyfriend in jaw. But this was very real.

The Santa Fe Sheraton exploded into panic and chaos as fists flew and Pam screamed. Everett’s loyal stunt boys and girls flooded the dance floor to help their boss. Meanwhile, the wrangler’s fellow horsemen charged in to get their guy’s back. We kept on playing, driving the Chicago blues into a frenzy. But as bodies collided and people fell, got trampled, and tables began to go over, all of us on stage saw it clearly:

The director’s 14 year-old daughter Crissinda (younger sister of Dean Cain and his younger guitar-scorching brother) got pinned against the wall with the crux of the fight trapping her in the line of fire. As she tried to protect herself, drunken wranglers, stuntmen, locals, and now the Hells Angels ignited into a battle royale — a bona fide Western barroom brawl.

As Crissinda was trapped against the wall to the right of the stage and PA speaker, her big brother Roger, unplugged the electric guitar and leapt off the stage into the donnybrook. There was something uncannily old Elvis movie about it, but everyone on stage began to follow suit. Like lemmings jumping off a cliff, we all launched into the spill. I think Kiefer was next, yanking the patch cord from his borrowed ax and leaping off-stage, like a young Jack Bauer, into the swell of bodies. Amplifiers were feeding back and whoever was on the drum kit kept on playing.

Meanwhile, the director Chris Cain — a former rodeo rider himself — and his wife Sharon, saw their daughter in danger, and they rushed to that corner. When the offending wrangler went down — he was hammered by Roger, Kiefer, Chris, and others — Sharon began kicking him with expensive tin-toed cowboy boots. Not just kicking him — this was snake-killing fury. Of course, this was her young daughter — who could blame her? The wrangler’s boys tried to help him, but the Hells Angels tore bodies away from the director and his daughter.

I don’t know if Lou Diamond Phillips jumped in before me or not, but I was soon down in the mix and I remember seeing Hells Angels taking down cowboys, and stuntmen trying to break it all up, only to take friendly fire. Lou, was trying to calm people amidst the flying fists. Dermott Mulroney came flying across a table and landed in the lap of my wife’s best friend Joey. As Joey recalls today, they would remain in that safe and cozy arrangement and watch the barroom brawl unfold.

Tables were crushed. Glasses were smashed. Cowboy hats were trampled on the floor. Glasses on the bar were also smashed, as were chairs. People had stampeded out to the lobby. All the while, the mic I had dropped before diving in, was still feeding back on stage, creating a high frequency, deafening tone over the mass scrum. And the drummer kept on.

And then it was over.

No police were called, but the bar was ordered evacuated and closed. There were bloody noses and cut cheeks, but everyone went off to their rooms or elsewhere. Local patrons were eager to get out of there. The lounge band was eager to collect their instruments and assess any damage.

With the lounge closed, I remained with the hotel manager, the director, his wife (who was still determined to find and destroy the cowboy who nearly hurt her daughter), and the Hells Angels. We let the hotel management know that we would pay all damages, and that we would take care of disciplining our own.

As quickly as the thing had exploded into a western bar brawl, it ended with the same kind of under-the-table, look-the-other-way resolve. Cisco, loyal to us with an almost tribal commitment, took Chris and I aside and asked if we wanted him and his guys to take care of anything. We had seen them, in past days, resolve a matter of a bitter local man starting up a chainsaw every time we called action (the Angels walked over into his backyard, the chainsaw stopped, and that was that) and we had seen them discipline a guy who tried to steal one of our movie horses. We had no doubt that they would follow-up with the wrangler, but we wanted it all to be done with.

The question came up about firing the wrangler who started it all. No, Chris said. No one’s getting fired. I’ll see everyone on set at call. Go home and get some sleep.

The next day, at the 5am catering truck, the set looked like a Mobile Army Surgical Infirmary; a few wranglers went hatless because they had stitches down their foreheads. More than one stuntman had an eye swollen shut like a fight club combatant. Our set medic was handing out pain killers as efficiently as Eddie was dishing out breakfast burritos. Everyone shook hands, let it go, and we got back to work. The outlaw ethos and code of “Pals” that drove the movie’s theme, carried over into our crew community.

Call it life imitating western movie art or vice versa; or call it the Curse of Billy’s Trigger Finger, buried somewhere in the geological strata and relocated bones and landfill underneath the Sheraton bar. But whatever happened that night might have been the last bona fide and epic western barroom brawl in American history.

To this day my wife says it was all my fault. And to never underestimate the dangerous potential of Chicago blues.